The avian use of restored oak woodland is a project I worked on during the senior year of my bachelor’s degree. It was the height of the Covid-19 pandemic and classes were online, so I needed a project I could do by myself with minimal materials. I contacted a local foundation asking to work on their land, and after receiving the green light, I set out to explore. As I strolled through the restored oak woodland, I quickly realized I wanted to do a biodiversity study. I’ve been a birder for a long time, so I was excited to take a closer look at the different bird and plant species there and see how they interacted with each other. Science isn’t always about fancy labs or high-tech equipment—sometimes it’s just about getting outside, observing, and recording what you see. I conducted this study with just my camera, phone, and knowledge of native birds and plants. This project turned out to be an amazing experience and helped me develop a deeper connection with an ecosystem I grew up around.

Introduction

Oak woodlands play an important role in California’s ecosystems and are home to many species, but vast sections of California’s oak forests have already been lost due to urban development, agriculture, lack of young trees, and sudden oak death. These woodlands are crucial habitats for disturbance-dependent bird species, which have declined significantly since European colonization of North America, and unfortunetly, only thirteen percent of California, or about seven million acres, currently contains oak forests, with over eighty percent on private land primarily used for ranching. Birds that are disturbance-dependent rely on natural phenomena such as wildfires or storms to clear out areas of dense habitat. When a habitat becomes too overgrown the lack of open spaces can affect food availability and species diversity. California is naturally a highly disturbed area that should get wildfires regularly. When wildfires occur often, they are able to clear out old grasses and shrubs creating open meadows and new usable habitats. Many trees in California, including native oaks, are fire-resistant and will survive natural wildfires. It’s only in recent years that fires have become so destructive because of decades of fire suppression and human interference.

Recent studies have found that increased competition with conifers, such as Douglas firs and western juniper, due to a lack of fire, has continued to degrade oak woodland habitat. Additionally, the increased occurrence of droughts in Oregon and California has placed significant strain on these ecosystems. As a result of habitat loss and degradation, small patches of restored habitat are becoming vital safe havens for many species. However, Fragmentation, which occurs when previously connected habitats become isolated due to human-made developments, still poses a significant challenge for wildlife. While many restoration efforts have successfully benefited generalist bird species, which thrive in a variety of habitats and utilize diverse food sources, specialist birds, which depend on specific habitats and niches, have been severely impacted. In this study, I aimed to determine how different vegetation structures within a restored area relate to avian species richness and diversity. Birds are usually able to return to patches quickly, and they are diverse and sensitive to environmental changes, so they serve as excellent indicators of habitat quality and restoration success.

Historically, oak woodlands have been dominated by cavity-nesting birds, which make up about 60% of individuals, despite comprising only about 25% of species. Cavity nesters rely on large trees, especially oaks, which are more likely to provide natural cavities for nesting. Other important species, such as acorn woodpeckers, also depend on large trees for granaries, but they have specific preferences for certain species. While there might be more individuals that rely on large trees, diversity is also crucial within a habitat. Different species often have varying preferences regarding the composition and structure of vegetation, so maintaining heterogeneity (diversity) within a habitat type is essential. Given that oak woodlands are important for California’s wildlife yet are being lost and degraded due to multiple factors, it is increasingly vital for managers to understand how species richness correlates with vegetation in managed areas. Promoting diversity is one of the best ways to keep ecosystems healthy. I hypothesized that there would be a positive correlation between avian species richness and more complex vegetation composition and structure.

Study Area

The area where I conducted my study is a nature reserve open to the public for recreational use. It is dominated by oak woodland, with about 15% consisting of upland grassland meadow. The most common tree species include blue oak (Quercus douglasii), interior live oak (Quercus wislizeni), and gray pines (Pinus sabiniana), while the most common shrub species are white-leaf manzanita (Arctostaphylos viscida) and poison oak (Toxicodendron diversilobum). The reserve is bordered by a creek on the west side and by suburban homes on all other sides. The foliage is thickest along the creek (riparian habitat) and thinnest along the suburban edge on the east side, where the area is most disturbed. Additionally, some areas near the southern edge of the creek were disturbed and recently cleared of underbrush. Various management practices were implemented to restore the area, including prescribed grazing, disking and planting native grasses, clearing underbrush, and spot spraying herbicides to control invasive plants.

Methods

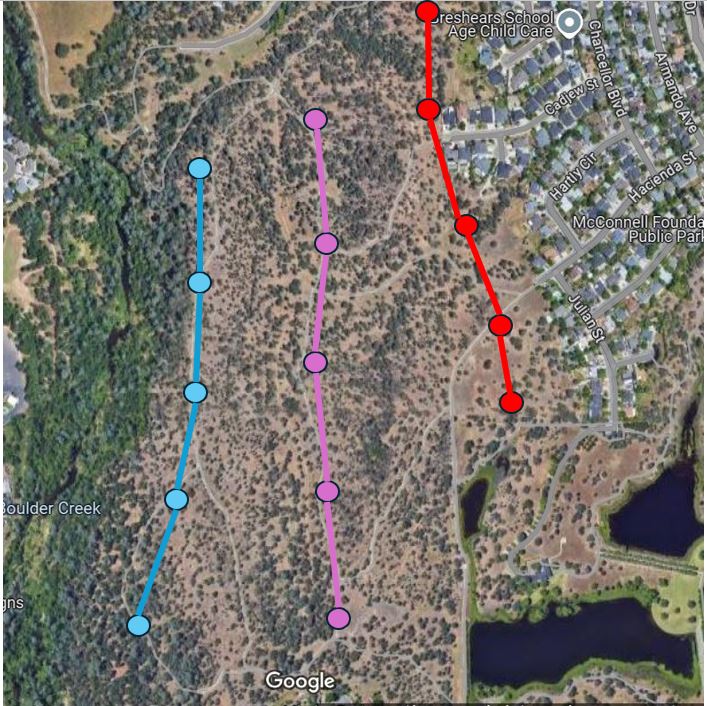

To get a better understanding of the bird and plant life in a restored oak woodland, I set up three transect lines based on how dense the trees were and how close they were to either the suburban homes or the creek. I named these the suburban edge, oak woodland, and riparian (creekside) woodland transects. Transects are a method of sampling the distribution and abundance of organisms in a natural environment. To create the transect, I set up a straight (or as straight as possible) line in my study area, then selected five equal-distant points along the transect line where I would stop and record everything I saw. In the end, I had a total of fifteen points where I gathered data.

Red = suburban edge

Purple = oak woodland

Blue = riparian woodland

For bird surveys, I visited each point once a week for 10 weeks and spent five minutes at each spot counting all the birds I could see or hear within a 50-meter radius. I also noted how many people were around, any other animals I spotted, and whether the area had been disturbed recently, as well as the weather. Vegetation sampling was a little simpler. Since plants don’t move, I only needed to do this once. At each point, I estimated how much of the area was covered by trees, shrubs, and grass in a 100-square-meter plot around my point. I identified each species of tree and shrub, measured the height of the trees using an app called Arboreal (which estimates height using triangulation), and measured the diameter of each tree trunk at breast height using a tape measure. These methods helped me collect data to get a detailed picture of both the bird and plant communities in each of the three areas.

Results

Over the course of 10 weeks surveying birds in a beautiful oak woodland, I recorded over 3,100 individual birds from 52 different species. Each survey location was always buzzing with bird activity, with at least four species present at all times.

When it comes to diversity, the reserve’s riparian woodland stole the show with the highest variety of bird species. The suburban edge and oak woodland areas also had healthy bird communities, but they didn’t quite match the diversity found near the water. One of the most common birds I encountered was the oak titmouse, appearing in an impressive 97% of my surveys and making up 14% of all the birds I counted. Acorn woodpeckers were also frequently spotted, showing up in 88% of the surveys. Together with the dark-eyed junco, these three species accounted for a significant portion of the birds in the reserve. Some species were more selective about where they hung out. Birds, like spotted towhees and ruby-crowned kinglets, preferred the creekside areas, while western bluebirds and European starlings were more likely to be seen near the suburban edge.

Interestingly, survey points that contained piles of cleared branches called slash piles attracted a surprising number of white-crowned sparrows. In one visit, I counted over 120 of them! After the slash piles were removed from one site, the number of white-crowned sparrows dropped dramatically, implying that the slash piles were an important habitat feature for them.

However, the main focus of the study was exploring how the vegetation around each point affected the bird populations. While no single factor fully explained the patterns, tree cover and shrub diversity seemed to play an important role. More trees tended to mean more birds, and a greater variety of shrubs was linked to higher species richness. In the end, it’s clear that many factors play a role in bird diversity and abundance.

| Common Name | Scientific Name | Frequency | Percent of Individuals |

| Oak titmouse | Baeolophus inornatus | 97% | 14% |

| Acorn woodpecker | Melanerpes formicivorus | 88% | 14% |

| Anna’s hummingbird | Calypte anna | 59% | 4% |

| Dark-eyed junco | Junco hyemalis | 55% | 10% |

| California scrub-jay | Aphelocoma californica | 50% | 4% |

| Ruby-crowned kinglet | Regulus calendula | 45% | 3% |

| Northern flicker | Colaptes auratus | 44% | 3% |

| White-crowned sparrow | Zonotrichia leucophrys | 41% | 9% |

| Lesser goldfinch | Spinus psaltria | 38% | 8% |

| House finch | Haemorhous mexicanus | 35% | 5% |

| Spotted towhee | Pipilo maculatus | 29% | 3% |

| European starling | Sturnus vulgaris | 29% | 4% |

| White-breasted nuthatch | Sitta carolinensis | 28% | 2% |

Discussion

Through my research, I found that the restored oak woodland reserve supports a healthy and diverse bird population, with a wide range of species spread across different areas. The most common bird species, like the oak titmouse and acorn woodpecker, didn’t show a strong preference for any one type of habitat. However, the riparian woodland area had slightly higher bird diversity, likely due to species that prefer dense vegetation, like spotted towhees and bushtits, which are commonly found along creeks and rivers.

On the other hand, birds like western bluebirds were more common in the suburban edge areas, where the habitat is more open and supports their feeding behavior. In contrast, areas with slash piles where vegetation had been cleared attracted high numbers of ground-feeding birds like white-crowned sparrows. These piles provide shelter, but they also skewed the bird diversity at these spots, showing that while useful, slash piles should be used sparingly to avoid imbalances in species diversity. When it came to understanding what influenced bird diversity and abundance, no single factor stood out. While tree cover and shrub diversity may play a role, as areas with more trees tended to have more birds, the results suggest that other factors could be influencing bird populations as well.

Over the past 50 years, oak woodlands have seen a significant decline in bird species, largely due to human expansion and habitat fragmentation. This makes it crucial for land managers to understand how to promote avian diversity in both restored and fragmented areas. A deeper understanding of how vegetation composition and structure can support a wider range of species is vital for effective restoration efforts. Many specialized bird species have struggled to adapt to smaller habitat fragments, while many generalist species have fared better. This highlights the need for strategies that focus on maintaining and enhancing biodiversity. Diversity is not just a measure of how many species are present; it’s a key indicator of the health and resilience of an ecosystem. By prioritizing bird diversity, managers can help ensure the future success of these vital habitats, ultimately benefiting the entire ecosystem.

Below is the full manuscript I wrote for this project. This manuscript is unpublished, so it has not been peer-reviewed or submitted to an academic journal.